Scraping A Website With Python - A Short Guide to a Short Script

I Need That Content

Despite working in and around the web platform for many years, I’ve (strangely) never had cause to extract data from the front end of a website - at least not to the extent where it’s been worth building a tool to do so programatically.

Recently I’ve been completely rebuilding a client’s website, including the back end. I like the architecture wrangling and design, less so the content stuff, but the nature of the mission meant I had a lot of blog-type News posts to port. The platform (a proprietary CMS) it currently sits on doesn’t have a export function which can pull out all their historic content in a useful way - nor does it offer direct db access.

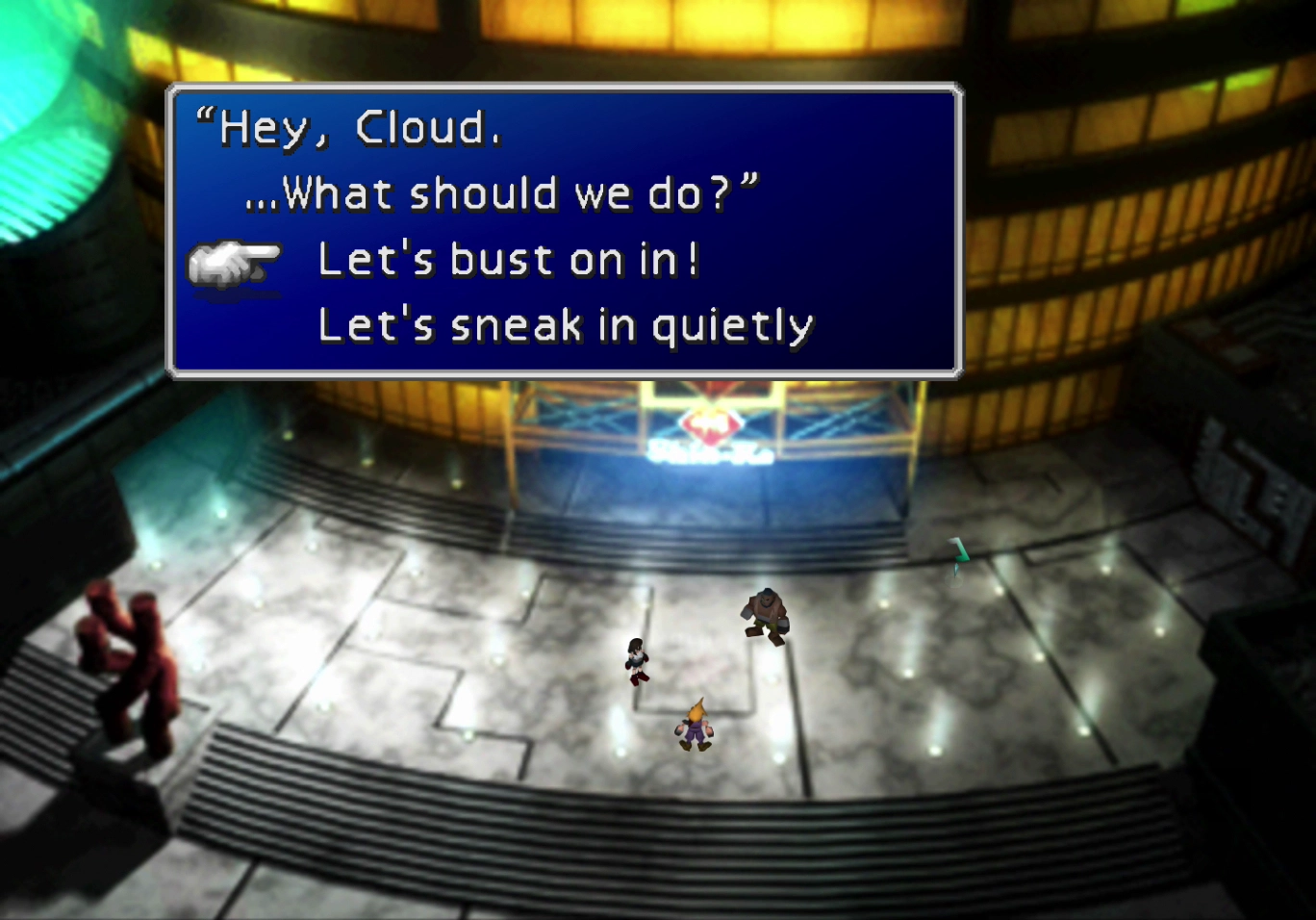

So, no sneaking the data out the back. Rather than delve into a boring admin process of seeing if that could be changed, I thought it could be more fun (and faster) to see how short I could make a script which would grab me that data and twist it into an importable format. Busting on in the front, as it were.

I’d already set up the new back-end with a CRUD API so I knew the shape I wanted the data in; all I had to do was pop it out. Here’s how I did it with what I hope are first-time friendly explanations.

Let’s Bust On In!

My home stack is .NET and everything that goes with it: enterprisey architecture, Azure deployments, strongly-typed C# and so on. For this kind of project, that’s just all too much. Python is really well suited to these kind of one-shot scripts and I’ve come to like the freedom of using something un-fussy when I’m making something that doesn’t really need maintenance, or collaboration - just a tool that only I will ever care about. It doesn’t need to be elegant, it just needs to work.

There’s a million ways to do this - this is how I did it.

I’m a long way from a python expert so I’m sure more proficient users will spot sloppy syntax and not-best-practice ways of doing things below. This ain’t a masterclass.

Planning the Script

The script needed to:

- Get me all the existing news urls, according to a pattern

- Grab the content html & images from each page, ignoring the template scaffolding

- Tidy up any oddities

- Get the data into a structured format ready to be programatically submitted to my API

Actually the last step could have been “submit directly to the API” but a) I wanted to preserve an archive and b) it’s never a bad idea to have the ability to make a few find/replace changes manually. These kind of scripts so often give you 98% of what you want and re-running the whole thing just to encompass an edge case I missed isn’t part of the game. This is supposed to be a break from the unit testing and future proofing of my production codebases, after all.

Still - it’s a simple enough plan. The next step was to leverage existing libraries best suited to the job. Not reinventing the wheel is always a good thing, and the other delight of these one-shot scripts is worrying about dependencies and long term reliability is not really a thing (not to say the packages I chose below are in any way flaky: they’re all well looked after and presumably here to stay).

Packages

I’ll briefly run through the packages / libraries one by one.

1

2

3

4

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import json

import re

Requests is perfect for this: make http requests, get responses. If you’re new to this, think “this is the computer visiting the url for me, and returning all the data”. Super easy to use.

BeautifulSoup is the real magic of the script. This fab library helps you traverse the DOM programatically, or in human speak, it can look at all the HTML data returned in the request (Document Object Model) in a highly sophisticated way, identifing and manipulating different elements as the program instructs. Read on to see some good examples.

json is the python module for encoding and decoding json (for my structured data output)

re is the python module for regular expressions, ‘regex’ (for helping find all the content urls)

Flow & Functions

Scripts like this, I know, don’t really need to be broken up much, but I’m a clean coder at heart so I have to stick to some of the basics. I broke up the plan into four functions (be grateful it’s not more):

1

2

3

4

def loop_through_archive(maxpages) # Work with the existing site's Pagination

def discover_news_urls(url) # Pull out href's matching a /news pattern

def process_page(url) # Get the stuff, make it readable, save it (could've been split up more)

def clean_up_string(string) # Deal with any weirdness

loop_through_archive

This is the most straightforward function; it’s really just a looping wrapper for the discover_news_urls() function. It’s got a maxpage variable (an int, in my mind but in anarchic, typeless python-land, anything at all) just so it can neatly stop at the final page.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

BASE_URL = 'http://burtcher.net'

def loop_through_archive(maxpage):

all_news_urls = set()

for page in range(1, maxpage + 1):

url = f"{BASE_URL}/news?page={page}"

print(f"Discovering news URLs on page {page}...")

news_urls = discover_news_urls(url)

print(f"Found {len(news_urls)} news URLs on page {page}")

all_news_urls.update(news_urls)

return all_news_urls

In ASP.NET Core, we ILogger everything. I love printing directly to the console instead. So edgy.

Very simply, we:

- Create a collection of somethings (

set()) with the nameall_news_urls - Loop through a

rangefrom 1 tomaxpage + 1 - In each iteration of the loop, bump up the pagenumber on the website’s news archive

url. - Create a new collection called

news_urlsand use it to catch whateverdiscover_news_urls()puts out when we feed that archive page’s url to it. - Add any discovered urls to the collection of

all_news_urlsand return it to the calling function.

discover_news_urls

This is where I get to use the fun libraries. The goal is to find any specific news pages by looking for occurences of the (slightly unusual) pattern “https://burtcher.net/{slug}/news” in the text of each archive page.

So assuming url is the archive page where we expect to find a few links to historic articles, we need to visit it:

1

2

r = requests.get(url)

r.raise_for_status()

That’s all there is to using the requests package (for something this simple anyway) - make a GET request with .get(). I then use the raise_for_status() method which will basically throw an exception if the http response isn’t a success code. This is a quick & useful thing for a low stakes script like this where I want it to break quickly if I’ve gotten the plumbing wrong and am feeding it bad urls (whereas in a big application there’d be a whole error handling and logging bit to shove in here).

So, if there’s no error we can assume we’ve gotten some page content into the r variable. To do something with it, we need to bring out the Soup.

1

soup = BeautifulSoup(r.text, "html.parser")

This creates an instance of BeautifulSoup to decode and then parse the HTML (passed in with r.text from the request). The soup object is a “parse tree” - a DOM that soup can read and manipulate, which is what we want. We’re going to run a fork through that soup and pick out the bits we need: in this case, urls to news articles. To do that, we’ll need to establish the pattern.

Hooray, regex:

1

NEWS_URL_PATTERN = re.compile(r"^https?://burtcher\.net/[^/]+/news/")

Calling the compile() method on re (the regular expression library mentioned earlier) and passing in a regex string creates a pattern which we can use to search stuff.

Note: I have never found regex syntax simple or memorable and explaining it is not something you want me to try and do (even if the above is basically the simplest example you could imagine). Perhaps it was always too easy to look up, so it never went in properly - but whatever the reason, it just will not stick in my head, despite it being brilliantly useful and the existence of some excellent resources to make it easy to learn. There are many things to say about AI but in this one very specific instance I can say I am excited that this is no longer something I have to care very much about.

With the pattern established and the soup ready for sifting, lets loop through soup:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

urls = set()

for a in soup.find_all("a",href=True):

href = a["href"]

if href.startswith("/"):

href = BASE_URL + href

elif href.startswith("http"):

pass

else:

href = BASE_URL + "/" + href

if NEWS_URL_PATTERN.match(href):

urls.add(href)

return sorted(urls)

What’s going on here?

- Create a new collection called

urlsto store any that we find. soup.find_all("a",href=True)returns a collection of<a>elements which match the filterhref=True, i.e., anchor tags which have an href attribute. This is the collection we then loop through.- For each of these tags, we first see if the link starts with “http”. If it does, we skip it (moving onto the next iteration of the loop with the

passkeyword). This is because, in the case of this site, all the links we want to collect are relative (e.g. “/news/whatever”), so any http links are going off-site. - For these discovered relative links, we prepend our domain and check to see if the result matches our pattern with

NEWS_URL_PATTERN.match(href). - If it’s a match, we can assume it’s a news article url, and add it to our array.

- Finally we return a sorted list using the native

sorted()method. Why? (If you’re wondering why, that’s fair. Habit, really. In this instance there’s no real reason to sort the results. Beware habits. But also don’t sweat the small stuff, sort if you want to sort.)

After those loops are done running, we’re left with the first layer of the prize: a list of real life news urls that we didn’t have to go figure out ourselves. Nice.

When Content Isn’t Content

Let’s think about the object model we’re trying to get any page data into. This is a simplified version of the C# DTO (Data Transfer Object) that my API endpoint is expecting to received:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

public class NewsPageDto

{

public DateTime Date { get; set; }

public string Title { get; set; }

public string Slug { get; set; }

public string ImageThumbnail { get; set; }

public string ImageMain { get; set; }

public string Body { get; set; }

public List<ContentBlockDto> AdditionalContent { get; set; } = [];

}

There are a few properties I’m not including here because they’re not relevant to the scrape, but you can imagine: Id, a Visibility bool, domain specific things etc.

The List<ContentBlockDto> type of the AdditionalContent property, if you’re not familiar with C#, is just declaring a collection1 of unspecified length of ContentBlockDto objects. The = [] syntax intialises the object with an empty collection to avoid null checking.

The (simplified) ContentBlockDto looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

public class ContentBlockDto

{

public string? ImageFile { get; set; }

public ImageSize ImageSize { get; set; }

public ImagePosition ImagePosition { get; set; }

public string? Content { get; set; }

public int Priority { get; set; }

}

The NewsPageDto is structured with this list of ContentBlocks, rather than just one big string prop for any html content, so that the content creators have some guided flexibility in what they’re making: through the CMS, they can add any number of content blocks with text & images formatted to certain predetermined specs to keep things looking consistent in the template.

So, what we don’t want is just to grab a big bunch of HTML and shove it up to our API as-is. The new website is exactly that: new. It’s got a new set of css styles to match these new data structures. Not only that, but because of the idiosyncracies of the existing CMS and the nature of user-input, there’s a lot of funky stuff in there that we don’t really want: empty paragraphs containing   (unbreakable space) characters, for example, which have been used to fudge the styling which we’re hoping to improve in the next iteration.

Our goal then is to extract the actual content as cleanly as possible, gleaning intent without necessarily copying the HTML structure.

process_page

This all matters to us because in process_page(), we’re going to need to tell soup how to identify these elements as they appear in the existing template so we can replicate them later.

We start the same way as before, making the get request, throwing errors if we don’t get a positive response code, and instantiating the html parser. We’re going to create a data variable to hold our output, too.

1

2

3

4

r = requests.get(url)

r.raise_for_status() # fail if httperror

soup = BeautifulSoup(r.text, "html.parser")

data = []

Now BeautifulSoup really starts doing all the heavy lifting. First, we’ll use it to find the parent element in the page where the content we want to capture lives. Remember, we don’t want to suck down all the header content, navigation and stuff like that - we just want the good stuff. Happily, we can get soup to zero in on an html element using traditional css selectors:

Finding the Content Element

1

for item in soup.select("div.newscontent"):

Here we ask soup to select from its parse tree any and all html elements which match the pattern ‘is a div’ and ‘has class newscontent’. (We hope it’s only one, as that’s what the template seems to allow for - but we can loop through more so let’s do that in case there’s an outlier).

So now we’re “in” the content area - it’s our current node. Whenever we reference item, we’re talking about the current (probably only) .newscontent div. Time to start getting at the content, and it makes sense to start with the title.

The Title

1

2

h1 = item.select_one("h1")

title = h1.get_text(strip=True) if h1 else None

Isn’t BeautifulSoup easy? .select_one("h1") returns the first matching html element (in this case an h1 tag) in the node, or None if it can’t find one. (It will: I’m not guessing, I know the template we’re working with and I know there will be an h1 tag and inside that tag will be the article title. There’s a version of this where you use some AI or heuristics to determine things like ‘where is x type of content in this page’ but that’s not what we’re up to here.)

We get the title variable by running .get_text() which pulls whatever’s inside the element into a python string. The strip=True argument functions like C#’s .trim(), removing whitespace before and after the string, so you’ve got something tidy.

The Main Body Content

Next, paragraphs. I know that inside this node, the ‘main body content’ is provided in the form of plain ol’ paragraph tags. So we want to get those, and only those.

1

2

3

4

paragraphs = []

for child in item.children:

if getattr(child, "name", None) == "section" and "contentBlocks" in child.get("class", []):

break # stop when we hit the contentBlocks

There’s a bit more going on here, so let’s walk through it step by step:

- We declare a

paragraphscollection to store extracted text (using a collection gives us freedom to reformat it later in life) - We loop through all the node’s

children(i.e., the elements immediately within it) - The first conditional makes sure we stop once we’ve gone too far. In this template, the main body content of

<p>tags is always followed by a social media area wrapped in a<section>tag with the classcontentBlocks. As we loop through the children, we want to look out for that and stop when we get to it.- Left side:

getattr(child, "name", None) == "section"will evaluate to True if the current child is a section tag. This works becausegetattr()returns the provided object’s .name if it exists, and None if it doesn’t. Tag objects in BeautifulSoup have .names - so if the child is something other than a tag, it’ll always return false. - Right side:

"contentBlocks" in child.get("class", [])pulls the child’s classes (we know, if we’ve made it to the right side, that we’re dealing with a tag) into a collection and checks to see if “contentBlocks” is present.

- Left side:

Again, the above belt-and-braces isn’t strictly necessary here; I don’t think it’s possible for any of these templated pages to not have this section immediately following the main collection of

<p>tags. But the point is that I don’t want to click through them all, so building in a little contingency costs very little and might save me a lot.

Next, we decide what happens when we do find what we’re looking for.

1

2

3

4

if getattr(child, "name", None) == "p":

text = child.get_text(strip=True)

if text and text != "\xa0": # skip empty and

paragraphs.append(str(child))

I’m using the same getattr() method to catch paragraph tags, then the .get_text() method we used on the title to pull out the content. I then run a little check to make sure the paragraph isn’t empty or just the nightmare-inducing unbreakable space character. I then pop the whole child onto my paragraphs collection (not the extracted text: I want to keep the html tags). Easy. When this loop runs, I should then end up with a list of non-empty paragraph tags in my collection.

I can then finalise the main body content of the article with this:

1

2

3

4

body = "".join(clean_up_string(p) for p in paragraphs)

def clean_up_string(string):

return string.replace("\r", "").replace("\n", "").replace("<p> </p>", "").replace("<p><p>", "<p>").replace("</p></p>", "</p>")

body ends up as a single string containing correctly tagged paragraphs without any newline characters, empty paragraphs or double tags (all things which appeared in the original template from time to time).

The

clean_up_string()method is very crude. I can probably do this much better using BeautifulSoup’s API. That is on the todo list next time I use the library.

Main Image

Like many templates, this one has a ‘main image’ which also doubles as the thumbnail for an archive view. On the new site, we’re going to reprocess all the images into multiple sizes and formats for a responsive, speedy display, so I don’t need to take both - I just need the primary image in the best resolution available.

With this template, it’s easy: there’s one img tag which precedes everything. By this point, the following code should be very readable.

1

2

3

mainImage = item.select_one("img").get("src") if item.select_one("img") else ""

if mainImage:

mainImage = BASE_URL + mainImage

We explicitly get the src attribute from the sole img tag, add our BASE_URL (because, again, it’s a relative link) and hey presto, we have the full image url.

Content Blocks

The image was a nice break. Content blocks require a little more thought, because we have some options. They might not exist at all, for one thing: many articles don’t have any at all.

Each content block we find might or might not have an image. If it does have an image, the image could be sized Large, Medium or Small and positioned Left, Center or Right.

Our options are pretty limited which is great but we have to account for each scenario. First, let’s make sure the contentBlocks section exists, and if it does, get each of the contentBlocks themselves - handily each in their own section with the class “contentBlock” - into a collection called blocks:2

1

2

3

4

5

contentBlocks = []

blockSection = item.select_one("section.contentBlocks")

if blockSection:

blocks = blockSection.select("section.contentBlock")

order = 0

See the order variable at the end? That’s there to make sure our content ends up in the same order it started. We’ll increment it as we loop through the blocks.

First let’s declare variables for the possible elements we’ll find:

1

2

3

4

5

6

for block in blocks:

content = ""

date = ""

src = ""

position = ""

size = ""

Then, in order, we’ll extract and clean up the content. This could be mixed html, so I’m using BeautifulSoup’s .decode_contents() method which gives us all the inner html of the selected element, including tags:

1

2

3

content_div = block.select_one(".content")

if content_div:

content = clean_up_string(content.decode_contents())

The date is also handily tagged up for us in (most) of these articles, but we want to make sure we’re saving a high utility date string (i.e. one which can be recognised and bound to a DateTime object in C#), so we’ll convert it on the fly using the datetime python module:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

date_tag = soup.select_one("p.date")

if date_tag:

date_str = date_tag.get_text(strip=True)

try:

date_object = datetime.strptime(date_str, "%d %B %Y")

date = date_object.strftime("%Y-%m-%d")

except ValueError:

date = None

The strptime method tries to parse a string into an actual datetime object, and the pattern I’ve passed in is telling it to assume the date_str variable is written in the format “31 December 1999”. The strftime is its opposite counterpart, formatting a datetime object into a string, this time outputting as “1999-12-31”, which can be a bit more reliably read without transformation when we’re doing something with the data later.

The image source (which will make adjust to an absolute url) and the size, which in this template is determined by a class on the img tag itself:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

image = block.select_one("img")

if image:

# Get an absolute URL

src = image.get("src")

if src:

src = BASE_URL + src

# Get a size class

size = None

for c in image.get("class", []):

if c.startswith("imagesize_"):

size = c.split("_")[1]

For the size, we cut the imagesize_xxx class into two using the underscore as the delimiter and take the second half

That’s all we really need for our ContentBlock, so we can append a new object to the collection we declared at the top of the loop, and increment the order variable ready for the next block:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

contentBlocks.append({

"content": content or "",

"img-src": src or "",

"img-pos": position or "",

"img-size": size or "",

"order": order

})

order += 1

Content Blocks complete. And that’s it - all the content is extracted, so all that’s left is to close the primary loop and return the data:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

data.append({

"title": title,

"date": date,

"image": mainImage,

"body": body,

"contentBlocks": contentBlocks

})

return data

Putting It All Together

To run the script from the command line, we use python’s (weird looking, to my eye) ‘main’ invocation if __name__ == "__main__":, which will run anything beneath it.

The final looping extraction, which gets all the news urls into a list, then loops through that list processing each page, looks like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

f __name__ == "__main__":

all_news_urls = loop_through_archive(40)

print(f"Found {len(all_news_urls)} news URLs.")

all_articles = []

for url in all_news_urls:

try:

articles = process_page(url)

all_articles.extend(articles)

except Exception as e:

print(f"Failed to process {url}: {e}")

Saving Structured Data with json

The final step couldn’t be simpler - we just encode the all_articles collection as a json object and save it into a new file:

1

2

3

4

with open("news.json", "w", encoding="utf-8") as f:

json.dump(all_articles, f, ensure_ascii=False, indent=2)

print(f"Saved {len(all_articles)} articles to news.json")

Opening up news.json shows something like the below, which is super digestible for any API.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

[

{

"title": "A Blog About Python",

"date": "2025-09-01",

"image": "https://picture.file",

"body": "<p>Here's a paragraph!</p><p>Here's another!</p>",

"contentBlocks": [

{

"content" : "<h2>Look At This Stuff</h2><p>Isnt it neat?<p><p>Wouldn't you say my...</p> ",

"img-src" : "https://picture2.file",

"img-pos" : "left",

"img-size": "small",

"order": 0

},

{

"content" : "<p><em>...collection's complete?</em>",

"img-src" : "https://picture3.file",

"img-pos" : "center",

"img-size": "right",

"order": 1

}

]

}

... etc

]

Wrapping Up

This turned into a fairly long winded way to describe something very simple - but it’s only simple because great libraries like request and BeautifulSoup do all the hard work. It took much longer to write out the blog post than it did the script, but hopefully it’s a worthwhile breakdown for anyone new to python scripting and/or web scraping (as I was). I’ll certainly consider going in the front to get necessary data much more readily now that I know how simple it is.

Thanks for reading. Shout me on the social links if you have to urge to correct one of my many errors.

Update: If you lke, you can now jump straight to the follow up article, where I demonstrate transforming the data and importing it to its final destination, also using a Python script, via the ASP.NET Core Web API.

Footnotes

There are several collection types in C#, of which

Listis just one. Feel free to go into the weeds on the various types and when they’re most useful. If you are like me, you will spend the rest of your life second guessing your choices. ↩︎“If you knew each contentBlock was a

<section class="contentBlock">, couldn’t you just have .select()-ed them all directly from theitemnode?” Yes, careful reader, I could have! If I’d looked ahead before starting writing the script I would’ve noticed it myself. Two lessons: 1) always plan before you start writing code 2) don’t get hung up on small stuff that doesn’t matter - I don’t mind sharing imperfect code; it’s quite liberating. ↩︎